Video games have long been literally the center of attention in the App Store, so Apple’s prospects for finding Arcade subscribers among its installed base of over 1 billion iOS devices is pretty straightforward. But can Apple Arcade spread the wealth of iOS’ developer attention to its other platforms, meaningfully driving new interest in gaming on Macs and Apple TV? Here’s a look at the future of macOS and tvOS games.

Arcade bridges Apple’s platforms

Apple’s triple platform Arcade

Apple has long known that most of the apps it sells in the iOS App Store are games. On the Mac App Store, however, games are far less plentiful and titles are more expensive, making them less likely to find casual adoption by tens of millions of players. Avid Mac players are more likely to buy games from Steam or at retail.

Really serious gamers have been more likely to consider a PC, where even more options abound in both titles and GPU options. That’s slowly changing as Apple has worked to enable external GPU support in macOS and promote its performance-optimized Metal API for GPUs.

On the gaming titles side, Apple Arcade is not only investing hundreds of millions of dollars to focus attention on gaming on iOS—it also links its other platforms together, giving users a strong reason to stay within its ecosystem by allowing them to resume gameplay of Apple Arcade titles between their different devices.

It’s not clear if every title in Apple Arcade will be playable on all three platforms, but given that cross-platform play is cited as a major feature of the new service, it looks like Mac and Apple TV support may be a requirement for Arcade developers, if not merely a strongly recommended suggestion. If that’s the case, Mac users will suddenly have a huge portfolio of games to play on their larger screen, as well as further incentive to use Apple TV to get the most from their Arcade subscription.

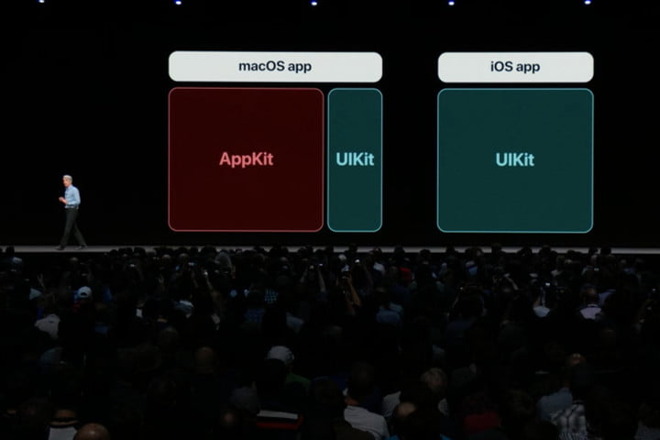

Last year, WWDC presented work to host UIKit apps on Macs

It appears that Apple Arcade may likely make use of Apple’s new UIKit on Mac initiative designed to make it easier to develop iOS titles that can be easily adapted to work on Macs. By “eating its own dog food” to deliver Arcade’s games on the Mac, Apple can finance the development and maturity of these portability frameworks, solving a real-world problem in gaming that will also be useful outside of gaming, in a variety of casual iOS apps that can add value to the Mac. We’re definitely going to hear more about the details of Arcade next month at WWDC 2019.

Previous flops to leverage gaming development across platforms

History suggests that simply announcing a cross-platform strategy won’t necessarily work out as expected. In 2015, Microsoft’s Universal Windows Platform similarly tried to leverage the installed base of its strongest platforms, Windows PCs and Xbox One, to deliver a sustaining library of software—including games—for its struggling Windows Mobile. It also created “bridges” designed to make it easier to port existing libraries of Android apps over, as well as to bring iOS code to Windows Mobile. There was broad consensus that UWP would work out swimmingly.

However, the UWP strategy wasn’t designed to port the huge volumes of native Windows x86 apps to Microsoft’s new mobile devices. It was instead based on 2012’s “Metro” apps, a new kind of portable code that could run on ARM-based Windows RT machines like the Surface RT, and Windows 8 PCs. But those platforms failed to garner much interest because there wasn’t a huge installed base willing to buy Windows Apps from Microsoft’s store. That meant that most developers preferred to keep selling regular x86-based Windows software, which could only run on PCs—because PCs were the only platform that really mattered. Both Windows RT and Windows Mobile died despite UWP’s intent to rescue them.

UWP didn’t spread PC success to phones and tablets and netbooks and whiteboards

Apple also once tried—and failed—to do something similar to get more games on the Mac. In 2007, before the App Store opened to sell mobile gaming for iPhone, Steve Jobs announced a partnership with EA Games to bring a series of Windows titles to Intel-based Macs. EA didn’t rewrite those titles for the Mac. Instead, it simply used TransGaming Technologies’ Cider virtualization to host existing Windows code on new Macs. That minimal effort resulted in at least seven titles EA could now sell to a new base of users, but didn’t really do much to establish the Mac as a serious option for gamers.

At the same time, games developers were creating their own cross-platform gaming engines to isolate much of their code from the underlying platform. That has increasingly enabled them to actually port more games to the Mac. In fact, next to EA’s Cider titles, John Carmack first demonstrated id Tech 5 at WWDC 07 performing state of the art rendering on a Mac. The first game to use it was Rage in 2011, which appeared for Macs along with game consoles.

Will Wright’s Spore Origins helped launched the iOS App Store in 2008

Existing game engines also facilitated adaptations of their existing titles to the iOS App Store. One of the first iPhone games to launch in 2008 was Spore Origins, a PC game that EA said it had moved to iPhone in just a couple weeks. So cross-platform tools can work, but there has to be commercial demand for developers to want to actually use them.

Demand, willingness to pay, capability to run

Over the last decade of the App Store, the demand for games on iOS has grown so dramatically that it’s changed how titles are launched. Apple’s iOS has chalked up a series of sophisticated exclusive hits, Including the trilogy of Infinity Blade titles from Epic Games that debuted in 2010, based on the Unreal Engine 3; Nintendo’s Super Mario Run in 2016; and Fortnight Battle Royale last year.

App Store demand was enough to prompt Nintendo to bring its games to iOS

Expectations that Android’s even larger installed base would win over developers’ primary attention have failed to materialize largely because iOS users were more willing to buy software, where Android users were overwhelmingly more likely to pirate titles. That generally kept Android titles at a lower quality or makes them ad-supported. And that has helped to stymie much interest in porting basic Android phone games into forms optimized for tablets or standalone consoles like the Shield, Ouya, Fire TV and even Google’s own Android TV initiative.

In addition to a hungry demand for games and a willingness to pay for them, the iOS installed base also represents a large base of high-quality, premium devices with impressive GPU power. There are Android flagships with competitive graphics and processing, but sales of premium Androids are a tiny fraction of the installed base. The majority of Androids sold are around $250, with anemic graphics and not enough RAM, and can only struggle to play simplistic puzzle games. Even many flagships fail to play games as well as similarly priced iPhones.

Changing the model funding games

Apple’s strong position in iOS gaming is due in part to purposely working to develop both iPhone and iPad optimized games. But while iOS is winning by a huge margin in mobile devices, Macs are treading water in gaming and Apple TV gets conspicuously minor attention from app developers. The Catch 22 for both tvOS and macOS games: until there are enough good titles, there won’t be enough active gamers on Apple TV or Macs to make it worthwhile to deliver compelling games at a workable price that enough players will spring for. Apple Arcade hopes to solves that by bringing an all-you-can-eat model that makes cross-platform play part of the bargain.

Apple Arcade could succeed where UWP, Cider, and Android failed because its subscription model can incentivize cross-platform titles by leveraging the global market opportunity of a billion iOS devices. While there’s “only” 100 million Mac users and something like 40 million Apple TVs in use, if Apple can make it relatively easy to deliver new Arcade titles that work across all of its platforms, it can radically make Macs and Apple TV more attractive to the same huge base of users who already buy the most games.

And because Apple’s cross-platform App Stores are doing the work of promoting, distributing, updating and billing, developers have a strong incentive to participate in making cross-platform gaming a success with great games that are fun to play mobile, on a Mac, or in the living room.

Changing the game

Additionally, by funding Arcade titles by subscription rather than by downloads or In-App Purchases or advertising, Apple can empower game developers to focus on fun gameplay, and to experiment with less conventional game types, play mechanics, and content subjects.

Currently, the mobile world—and increasingly PCs and consoles as well—are awash with “safe,” formulaic gaming titles that are already known to appeal to mainstream audiences. There’s so much risk in experimenting outside of the status quo that nobody really wants to speculatively fund unproven new concepts.

Mobile games, in particular, have largely settled on the model of free games that exploit addiction psychology to push players to buy IAP or gamble with “loot boxes.” This perversely incentivizes games that grow more commercially successful as they become less fun and more aggravating and expensive to play. Arcade’s subscription gaming appears to be the same price no matter what games you play, which should induce the creation of fun and creative titles over exploitive and manipulative shovelware, or the adware that cheapens gaming on Android.

By changing the business model of gaming, Apple can fund games that are more broadly appealing to different types of audiences, and even discover new styles of creative gaming that haven’t yet found a way to financially exist. The company highlighted this at Arcade’s introduction, citing a series of developers (above) who echoed the sentiment that their Apple Arcade projects simply couldn’t launch elsewhere. And Apple has also made a clear commitment to deliver games with no ads and no surveillance tracking to sell you as a product.

[“source=appleinsider”]