The Facebook post is a reflection of what we project but what we search on Google is a testament to what we are at our most insecure (and honest) (File Photo)

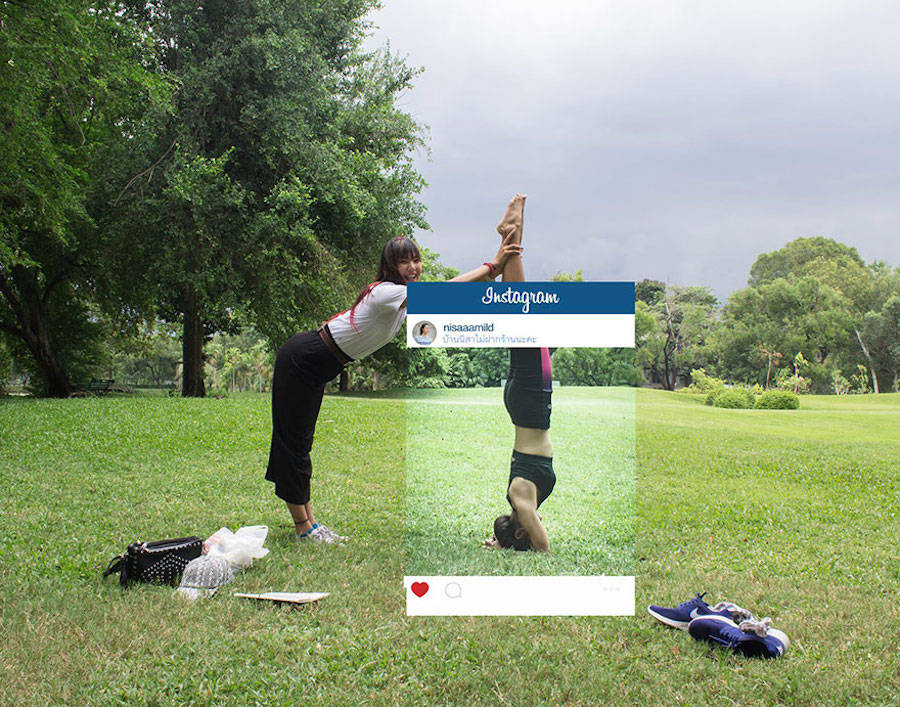

Be it Snapchat stories, Instagram or Facebook— we are used to constructing the beautiful versions of truth with social media. We understand and follow the unwritten rules. Positivity, inspiration and beauty in the form of travels, get-togethers, weddings and babies are very well received. Expressing sadness upon events like passing away of a family member are also acceptable and resulting in outpouring of condolences and virtual hugs. However, social media is not a place for ambivalence and insecurities such as economic hardships, relationship tensions or difficult pregnancies. Those sides of us are never meant to percolate on social media. If someone does post such things, it tends to raise eyebrows. Imperfect views — without appropriate cropping out and edits — also generally don’t fit the bill for posts. So the social media versions of us are a near-perfect, neat facade for others to see and they are usually made up of very specific moments that represent the best of the best, with little context.

Users can try to find solace in this representation. “I spend way too much time on it, especially … when I myself am uncertain. I maybe post more than I used to because I am trying to soothe myself by presenting myself as fine,” writes a user on Medium. It creates a rift between the real person and their representations. “The curated lives that we post have real consequences in our actual lives,” says journalist and RJ, Shankar Vedantam on NPR’s Hidden Brain podcast. While no telling of benefits of social media is required, there is a cost, he says, “As you see the seemingly idyllic lives of your friends you may feel that your vacations are dull by contrast. While your relationship seems grey, theirs appears to be in technicolour”.

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, a data scientist and author of Everybody Lies, who has worked extensively with Google data, finds a huge disparity between top posts on Facebook and top searches on Google — while the former is often a reflection of what we project, the latter is a testament to what we are at our most insecure (and honest).

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, a data scientist and author of Everybody Lies, who has worked extensively with Google data, finds a huge disparity between top posts on Facebook and top searches on Google — while the former is often a reflection of what we project, the latter is a testament to what we are at our most insecure (and honest).

Stephens-Davidowitz found many insights from the truth serum of Google. For instance, referring to how wives speak of their husbands, he writes, “On Social media, the top descriptors to complete the phrase ‘My husband is …’ are ‘the best,’ ‘amazing,’ ‘my best friend,’ ‘the greatest’ and ‘so cute’. On Google, one of top autocomplete suggestions to the same phrase is also ‘amazing’, he writes, adding, “The other four: ‘a jerk’, ‘annoying’, ‘gay’ and ‘mean’”.

Of course, as we become seasoned users, most of us become dimly aware that the grass usually appears greener in Facebook profiles of others. Nevertheless, we end up comparing ourselves to others.

Studies show that in spite of making a mental adjustment for the discrepancy between real and constructed lives of others, the act of comparison itself diminishes people’s happiness. Researcher Ohad Barzilay and his colleagues of Tel Aviv University in Israel studied the employees of a firm where they were completely debarred from having a Facebook account due to security reasons. The employees had to delete their accounts to continue working for the company. The firm then decided to allow some employees to reopen their accounts, which created two random groups of users and non-users. The researchers collected data from the firm’s employees in the next few months, focusing on social comparison and their perception of others’ lives and happiness. They found that Facebook usage increases users’ engagement in social comparison and consequently decreases their happiness. These users seemed to understand well that people present a better version of themselves in their profiles. In spite of that they became less happy over time compared to those who were prevented from using Facebook. “You need to prove yourself to yourself over and over again and this makes you less happy”, Barzilay says on the podcast. It means that just having a good time is not enough — one feels the need to take a picture of it and post it and get others’ reactions in order to feel as good as their friends. The very act of comparison takes them out of the experience.

Experiments by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania indicate that scouring others’ social media posts can also generate a comparative anxiety that one’s friends are having happier, meaningful experiences without them, even if it may be a routine activity — a phenomenon better known as FOMO — Fear of Missing Out. For instance, one may be in an amazing destination and having the time of their lives, but returning to the hotel and looking at a picture of their friends, on social media, enjoying a regular night out, may dim the feeling of ecstasy from their own eventful day. It’s the slightly dampening feeling of ‘I wonder what they did without me’ — the FOMO, which takes them away from the present and indeed ‘miss out’.

Knowing things about others, without context, leaves room for dampening self-doubts. So while the fictional worlds of our friends may be making us feel inadequate, it works both ways. Our own moment curations also likely have similar impacts on others. And it goes on.

[“Source-indianexpress”]