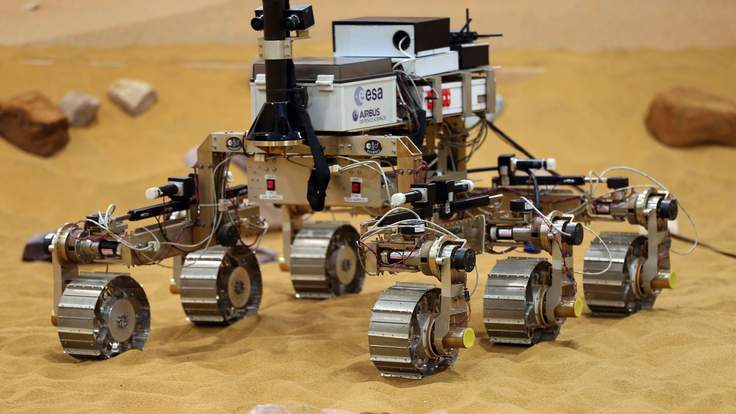

A Mars rover built in Britain and called Bruno is helping scientists who want to explore the Red Planet.

It belongs to a “family” of three rover prototypes – the others are called Bridget and Bryan – which are testing the latest planetary navigation technology.

The research will help the team launch a six-wheeled machine, which is similar to Bruno, to Mars in two years’ time.

Once there, it will hunt for signs of life in soil samples below the Martian surface, and take detailed colour images of the landscape.

Assembling the mechanical parts and electronic circuits is due to begin at the UK headquarters of Airbus Defence & Space in Stevenage later this year.

The rover is being tested in a hangar

The rover prototypes have been tested in a giant hangar containing 250 tons of sand, dotted with artificial boulders.

The rover’s top speed is two centimetres per second.

Video:

The firm’s head of science Dr Ralph Cordey said: “One of the challenges of going to Mars is that it’s so far away in terms of the time it takes radio signals to go there and back – around 40 minutes.

“It’s not possible to drive this sort of machine with a joystick. You’ll crash it. So this rover is designed to be semi-autonomous.

“It can produce its own 3D map of the area ahead of it, look where it’s being asked to go, and plot its own path.

“It’s aware that some rocks it can’t get over and has to drive round, and it can see ditches and sense what slopes are safe to climb.”

The rover currently gets confused by shadows, which is why human involvement is still necessary.

Next month British astronaut Major Tim Peake, who is orbiting the Earth as part of the crew of the International Space Station, will get to operate Bruno remotely from space.

He will be asked to drive the rover into a “cave” simulated by plunging half the Mars sandpit into darkness.

The finished rover will have a drill that can bore two metres below the Martian surface and extract samples to be analysed in its on-board laboratory.

The ExoMars rover will look for biochemical signatures of life, such as organic molecules with structures that indicate a biological origin, or specific minerals left behind by ancient microbes.

Dr Cordey said: “The surface of Mars is not a nice place for life. There are cosmic rays that bombard the surface, and energetic particles from the sun, and the surface chemistry is very reactive so that any organic material would be rapidly oxidised.

“The place to look for life is under the surface, and that’s what this mission is doing that no other mission has.”

[Source:- Skynews]