For just over a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nature highlighted key papers and preprints to help readers keep up with the flood of coronavirus research. Those highlights are below. For continued coverage of important COVID-19 developments, go to Nature’s news section.

30 April — One vaccine dose can nearly halve transmission risk

A single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine made by either Pfizer or AstraZeneca cuts a person’s risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to their closest contacts by as much as half, according to an analysis of more than 365,000 households in the United Kingdom.

Although the vaccines have been shown to reduce COVID-19 symptoms and serious illness, their ability to prevent coronavirus transmission has been unclear. Kevin Dunbar, Gavin Dabrera and their colleagues at Public Health England in London looked for cases in which someone became infected with SARS-CoV-2 after receiving a dose of either vaccine. They then assessed how often those individuals transmitted the virus to household contacts.

The team found that people who had been vaccinated for at least 21 days could still test positive for the virus. But viral transmission from these individuals to others in their households was 40–50% lower than transmission in households in which the first person to test positive had not been vaccinated. Results for the two vaccines were similar. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

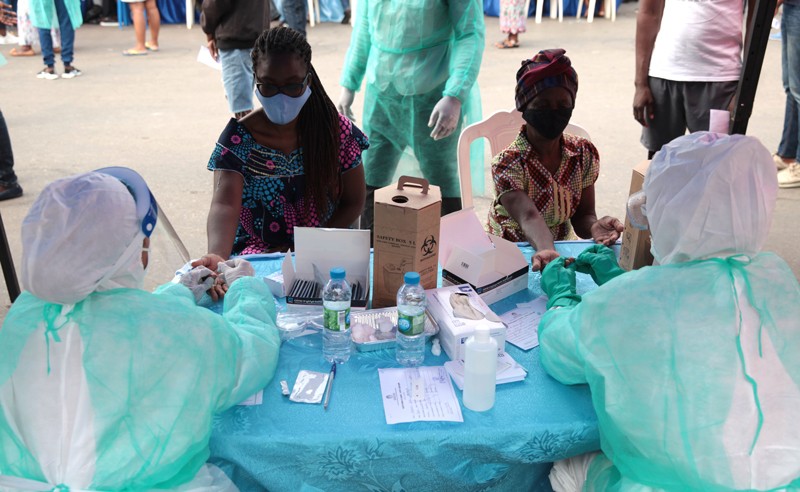

29 April — A Chilean city’s COVID toll reflects its vast inequalities

In Santiago, COVID-19 dealt the hardest blow to people with low socioeconomic status, because of factors such as crowded households, a lack of health care and an inability to work from home.

Death rates were greater in low-income areas of Santiago, especially among people under age 80, than in high-income areas, according to research by Gonzalo Mena, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues. The team found several explanations for this disparity. Compared with higher-income areas, lower-income neighborhoods had high rates of positive SARS-CoV-2 tests. This suggests that testing there was inadequate — and therefore that efforts based on case numbers to curb the epidemic couldn’t be appropriately targeted.

Low-income areas had one-quarter as many hospital beds per 10,000 people as did wealthy areas. And a striking 90% of COVID-19 deaths in lower-income areas occurred outside of health-care facilities, compared with 55% in a more affluent area of the capital.

Finally, by using location data from mobile phones, the team found that people in low-income areas moved more during periods when residents were supposed to stay at home — possibly because more people had jobs outside of the house.

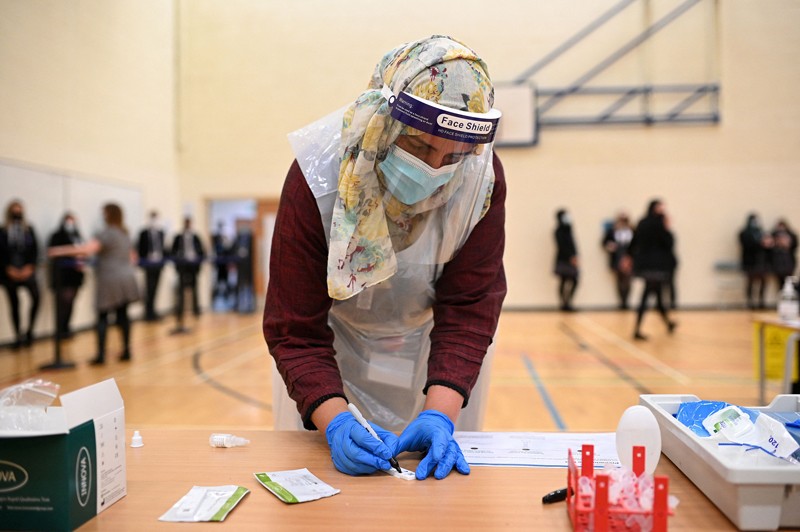

28 April — Self-taken swabs can track a pandemic’s hidden patterns

Regular swabbing of a random sample of the population quickly detects the resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 infections, even in young adults.

Steven Riley and Paul Elliott at Imperial College London and their colleagues tested nose and throat samples from 594,000 randomly selected UK residents, who swabbed themselves or their children between 1 May and 8 September 2020. The study found that, during that time, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate dipped as low as 0.04% in the tested population — down from around 5% in early 2020 at the height of the United Kingdom’s first wave — and then began climbing to a peak of about 0.13% in the final round of testing.

Prevalence rates early in the second wave were highest among young adults aged 18–24, at 0.25%, compared with 0.04% among those aged 65 and older. This suggests that increased socializing by younger people probably drove the resurgence. These age patterns were not reflected in data from routine surveillance at health-service providers, which underestimated infection rates in younger age groups.

The researchers say that their study demonstrates the benefit of large-scale community testing in providing an early warning of spikes in infections, even at low levels of transmission.

27 April — How to predict a vaccine’s success without a large trial

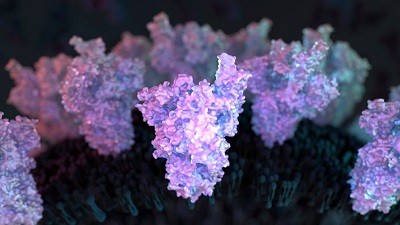

Moderna’s vaccine provides protection against COVID-19 by triggering the production of antibodies against a key viral protein, a study in monkeys suggests. The insight — if confirmed in humans — could speed the development of next-generation vaccines.

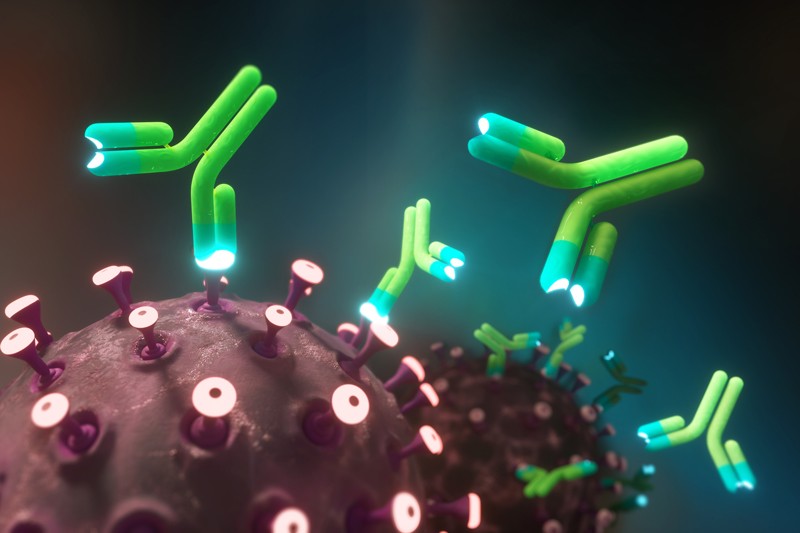

Vaccines can trigger diverse immune responses, including the manufacture of antibody molecules that bind and block infectious viruses, and the activation of T cells that kill virus-infected cells. By identifying the immune responses that can predict a vaccine’s success, scientists could more easily judge candidate vaccines.

To identify which immune responses are important for Moderna’s vaccine, Barney Graham and Robert Seder at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, and their colleagues gave monkeys a range of vaccine doses and exposed the animals to SARS-CoV-2 (K. S. Corbett et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/f8pf; 2021). The vaccinated animals that had the lowest levels of viral genetic material in their noses and lungs also had the highest levels of antibodies that recognize the viral spike protein, the molecule that the Moderna vaccine encodes. Levels of other immune markers did not correlate as strongly with the vaccine’s protective effects. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

A parallel study now under way will compare immune markers in people who were protected by jabs, including the Moderna one, with markers in people who were infected despite receiving a vaccine. Identifying these ‘correlates of protection’ will help researchers to assess existing and future vaccines without running costly, large-scale clinical trials.

23 April — A care-home COVID outbreak shows a vaccine’s powers

In a real-world test, an mRNA-based vaccine protected care-home residents and staff against a new SARS-CoV-2 variant.

On 1 March, an unvaccinated health-care worker at a Kentucky care home tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. At that time, 90% of the home’s residents and 53% of its health-care workers had received their second dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine; the vast majority had received their second shot more than 2 weeks before the worker’s infection was identified.

Alyson Cavanaugh at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and her colleagues report that 46 of the 199 people at the care home were infected during the outbreak. The researchers estimate that the vaccine was 86.5% and 87.1% effective at preventing COVID-19 among residents and staff, respectively, who were more than 2 weeks past their second dose. The shots were even more effective at preventing hospitalization, although one vaccinated resident died.

Genome sequencing of samples from 27 individuals identified a variant circulating during the outbreak known as R.1, which contains mutations that have been linked to increased transmissibility and immune evasion.

22 April — Previous infections could shorten COVID illness

Recent infection by viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 could reduce the duration of COVID-19, according to an analysis of antibodies from 2,000 health-care workers.

Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein can be powerful defences against COVID-19. But some people have rare antibodies against other coronaviruses that pre-date the pandemic and can bind to SARS-CoV-2 proteins other than spike. To search for a possible link between such antibodies and protection from COVID-19, Scott Hensley at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and his colleagues studied antibody levels and infection status in about 2,000 local volunteers during two COVID-19 surges .

The team found that people with the rare, pre-pandemic antibodies that work against SARS-CoV-2 were not protected from contracting the virus and developing COVID-19. But high concentrations of other antibodies that had been elicited by two betacoronaviruses — a category that includes SARS-CoV-2 — were associated with a quicker recovery from COVID-19 symptoms.

The authors speculate that this protection is provided by immune-system players called T cells that were generated in response to previous betacoronavirus infection. The results have not yet been peer reviewed.

15 April — Common asthma medicine could shave days off COVID illness

A clinical trial in more than 4,600 people at risk of serious COVID-19 found that an inhalable asthma medication shortened the duration of disease symptoms by about 3 days.

The asthma drug budesonide is an inexpensive and widely available inhalable steroid. Christopher Butler and Richard Hobbs at the University of Oxford, UK, and their colleagues tested budesonide in people who had COVID-19 symptoms but were not hospitalized.

Participants either were over the age of 65 or were more than 50 years old and had conditions that increased their risk of COVID-19 complications. Participants were randomly assigned to either receive the drug or serve in a control group, but none took a placebo. Both participants and investigators knew who had received the drug.

Those who took budesonide twice daily for two weeks reported that their COVID-19 symptoms ended three days earlier than those who did not use the steroid. The results have not yet been peer reviewed.

14 April — COVID vaccination scheme keeps variants under control

Israel’s world-leading vaccination programme seems to be keeping worrying coronavirus variants at bay.

More than 60% of people in Israel have received Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and case numbers are plummeting. But new variants such as B.1.1.7, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, are also circulating in Israel. To determine their effects, a team led by Adi Stern at Tel Aviv University and Shay Ben-Shachar at the Clalit Research Institute in Ramat Gan, both in Israel, analysed ‘breakthrough infections’ recorded among several hundred vaccinated people.

Multitude of coronavirus variants found in the US — but the threat is unclear

Almost 250 of the breakthrough infections were in people who had received just one of the two recommended doses of vaccine. The researchers compared these infections with the same number of infections in unvaccinated individuals who were matched for age, date of infection and other characteristics. The comparison found that infections in partially immunized people were slightly more likely to be caused by B.1.1.7 as were those in unvaccinated people.

The researchers also studied 149 breakthrough infections in people who had received both vaccine doses. Eight of these infections were caused by the B.1.351 variant, first identified in South Africa. Just one infection out of 149 in matched, unvaccinated controls was caused by the variant, suggesting that the vaccine is less effective against the variant B.1.351 than against other variants.

Rates of B.1.351 infection remained very low and did not rise during the study, the researchers say, suggesting that vaccination and other interventions kept the variant in check. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

12 April — Quick tests show value for stopping COVID’s spread

Rapid COVID-19 tests can detect most coronavirus infections that will lead to further transmission, according to simulations incorporating the results of more than 3.5 million coronavirus tests.

Rapid coronavirus tests performed by hand-held test kits called antigen lateral-flow devices could bolster test-and-trace programmes. But such tests are less effective at detecting infections than are slower, gold-standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests.

David Eyre and Tim Peto at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, UK, and their colleagues analysed testing and contract-tracing data collected in England from 1 September 2020 to 28 February 2021. The study included data from about one million people with positive coronavirus PCR tests and the results of PCR tests from about 2.5 million other people who had come into contact with them.

The team used data on the performance of lateral-flow devices to estimate that the most sensitive rapid tests could have detected nearly 90% of cases that led to an infected contact. The team also found that people with higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 in their bodies tended to be more infectious than people with lower levels.

Infection with the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, increased transmission by about 50%. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

9 April — Sputnik V vaccine is no match for a fast-spreading variant

A coronavirus variant that was first detected in South Africa can evade antibodies elicited by the Sputnik V vaccine against COVID-19.

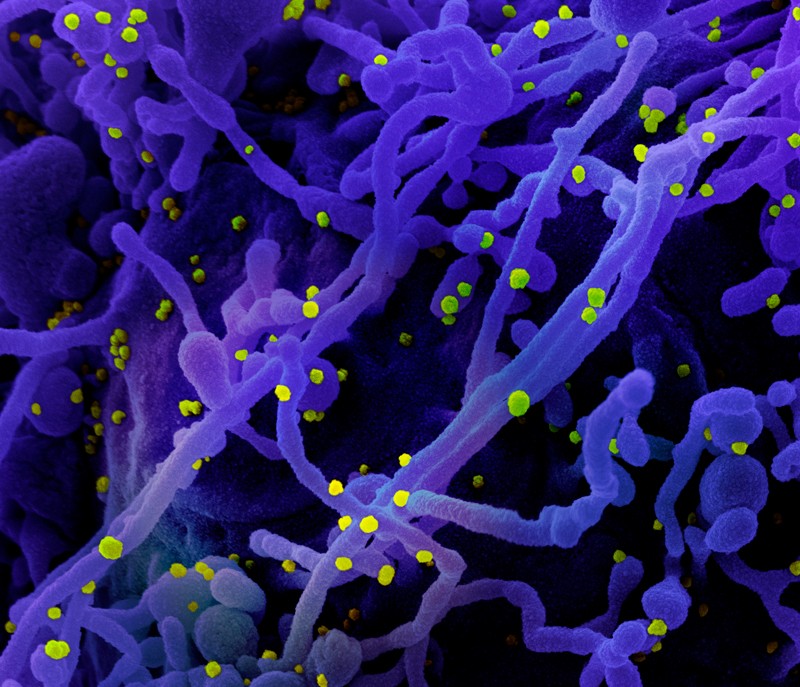

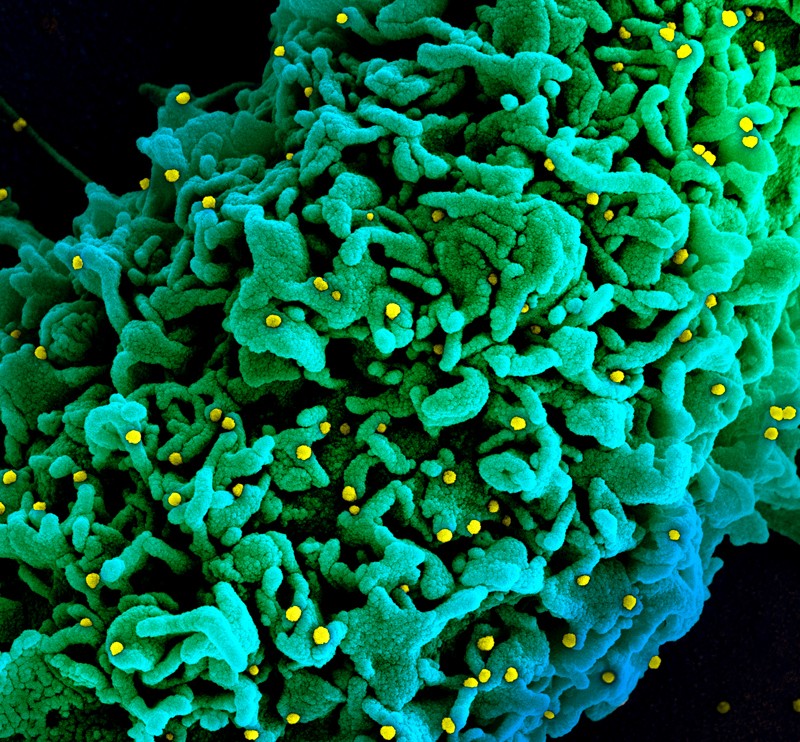

Many vaccines — including Sputnik V, developed by the Gamelaya National Centre for Epidemiology and Microbiology in Moscow — trigger the production of antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 protein called spike, which the virus uses to infect host cells. Scientists worry that the vaccines might be ineffective against SARS-CoV-2 variants with mutations in the spike-encoding gene.

Benhur Lee at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and his colleagues obtained samples of antibody-laden blood serum from 12 people vaccinated with Sputnik V (S. Ikegame et al. Preprint at medRxiv. The authors then tested the serum against benign viruses engineered to make the versions of spike found in certain SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The team found that 8 of the 12 samples did not inhibit viruses equipped with spike from B.1.351, the variant first identified in South Africa. But the samples did effectively overcome viruses with spike from B.1.1.7, a variant first detected in the United Kingdom.

The emergence of new variants might require the development of a new generation of vaccines, the authors say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

8 April — New coronavirus variants muscle aside potent antibodies

Fast-spreading coronavirus variants identified in California blunt the antibody response triggered by vaccines.

In early 2021, researchers studying coronaviruses collected in California spotted a pair of SARS-CoV-2 variants that share several mutations affecting the spike protein, which the virus uses to infect cells. The variants, B.1.427 and B.1.429, have been identified in 30 countries and most US states and, by February 2021, accounted for more than half of the SARS-CoV-2 viruses sequenced from California.

To better gauge any threat posed by the variants, David Veesler at the University of Washington in Seattle and his colleagues conducted laboratory tests of the variants’ ability to elude infection-blocking molecules called neutralizing antibodies. The tests showed that neutralizing antibodies generated by people who had received two doses of either the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine were, on average, three times less potent against viruses with the spike-protein mutations found in B.1.427 and B.1.429 than against viruses lacking those mutations. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

Rare COVID reactions might hold key to variant-proof vaccines

Xiaoying Shen and David Montefiori at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, and their colleagues conducted a separate investigation into how B.1.429 responds to antibodies. The team pitted the variant against neutralizing antibodies from three sources: people immunized with the Moderna vaccine, people immunized with a vaccine made by Novavax and people who had recovered from COVID-19. Laboratory tests showed that B.1.429 was more resistant to inhibition by all three sets of antibodies than was a strain of the virus that circulated earlier in the pandemic.

The reductions in antibody potency are similar to those observed with a variant called B.1.1.7, which was first identified in the United Kingdom. Current vaccines are highly effective against B.1.1.7, suggesting that they are likely to remain so against the variant identified in California, Montefiori’s team says.

7 April — Antibodies triggered by Moderna vaccine last for months

The mRNA-based Moderna vaccine spurs an immune response that persists for at least six months.

The two-dose vaccine made by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been shown to be 94% effective at preventing COVID-19. To learn whether the vaccine provides lasting protection, Mehul Suthar at Emory University School of Medicine in Decatur, Georgia, and his colleagues studied antibodies collected from 33 people who received the vaccine during an early phase of testing.

Three types of test showed that participants still had antibodies against the coronavirus six months after receiving their second dose of the vaccine. For example, antibodies from all participants, including those in the oldest age group, could inhibit a modified version of SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory. The authors are now studying whether antibodies elicited by the vaccine last for more than six months.

6 April — Air traveller yields a new variant bristling with mutations

A coronavirus variant identified in Angola carries more mutations than any strain previously identified.

A team led by Tulio de Oliveira, at the University KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa, and Silvia Lutucuta, at the Angola Ministry of Health in Luanda, identified the variant after sequencing samples from three people who flew to Angola from Tanzania in February 2021. The variant, named A.VOI.V2, carries 34 mutations, including 14 in the spike protein, which the virus uses to infect cells.

The variant deserves further study, the authors say, because it carries mutations that might help it to escape some people’s immune responses. The finding has not yet been peer reviewed.

2 April — A nation’s race to vaccinate adults protects unvaccinated kids too

Vaccinating many people against SARS-CoV-2 could stall infection rates even among unvaccinated children in the same community.

Last December, Israel launched one of the fastest vaccination schemes in the world, reaching 50% of the population in 9 weeks. But only people aged 16 and over were eligible for the jab.

To test the ripple effects of widespread vaccination, Tal Patalon at Maccabi Healthcare Services in Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, Roy Kishony at the Technion — Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa and their colleagues analysed COVID-19 vaccinations and test results recorded between January and March 2021 for people in 223 Israeli communitie. In each community, the authors examined the relationship between the vaccination rate in adults over three 3-week intervals and the rate of positive results for a COVID-19 test in children 35 days later.

The authors found that, in the weeks after older people had received the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine, the infection risk among children under 16 dropped proportionally to the percentage of adults who had been vaccinated. The authors warn that their results might be influenced by children who had previously been infected, even though the study included communities with low infection rates. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

30 March — New coronavirus variants spur multi-talented antibody response

Antibodies from people infected with the 501Y.V2 coronavirus variant first identified in South Africa are also effective against previously circulating variants, suggesting that vaccines against 501Y.V2 might work against a range of coronavirus variants.

South Africa’s first wave of coronavirus infections peaked in July 2020. The second wave peaked in January 2021, and was driven by the recently discovered 501Y.V2 variant (also called B.1.351). The variant is partially resistant to antibodies against previously circulating variants, raising concerns about the effectiveness of current vaccines against it.

Tulio de Oliveira at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa, Alex Sigal at the Africa Health Research Institute, also in Durban, and their colleagues tested blood plasma from people in South Africa who had been infected during one of the two waves. The team found that plasma from the second wave was 15 times more effective at preventing the 501Y.V2 variant from infecting cells in a laboratory dish, compared with plasma from the first wave.

The scientists also found that second-wave plasma could neutralize first-wave variants with an effectiveness similar to that of the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine. This implies that updated vaccines against 501Y.V2 could also protect against earlier coronavirus variants.

30 March — ‘Real-world’ study finds vaccines sharply cut infection risk

A full vaccination reduces risk of coronavirus infection by roughly 90%, according to a study of US nurses, firefighters and other front-line workers who received an mRNA-based vaccine.

Clinical trials have shown that the mRNA-based vaccines made by Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech are highly effective at protecting people from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. To learn whether the vaccines also shield people from becoming infected in the first place, Mark Thompson at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues studied SARS-CoV-2 test results from nearly 4,000 people whose work puts them at high risk of infection.

Study participants were vaccinated between mid-December 2020 and mid-March 2021. After vaccination, they swabbed their own noses for viral testing once a week for 13 weeks. Participants were considered fully immunized two weeks after receiving their second dose of vaccine.

Full immunization was 90% effective at protecting people against infection, and a single dose was 80% effective. But the researchers caution that because very few participants became infected after vaccination, it’s difficult to state the vaccines’ effectiveness against infection with high precision.

25 March — Coronavirus antibodies last for months — if you have them

The neutralizing antibodies that the immune system produces to disable the virus SARS-CoV-2 can last for at least nine months after infection, but not everyone makes them in detectable quantities.

Chen Wang at Peking Union Medical College in Beijing and his colleagues took blood samples from more than 9,500 people in some 3,500 randomly selected households in Wuhan, China, the first place known to be widely affected by COVID-19 (Z. He et al. Lancet 397, 1075–1084; 2021). The team took samples at three separate times over the course of 2020: once in April, after the city’s lockdown lifted; once in June; and again between October and December. The team tested the samples for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which indicate that a person has been infected with the virus.

The researchers found that only 7% of the population had been infected with the virus, of whom more than 80% had had no symptoms. Around 40% of the infected people produced neutralizing antibodies that could be detected for the entire study period.

The researchers conclude that most people in Wuhan are still susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and that a mass vaccination campaign is needed to achieve herd immunity.

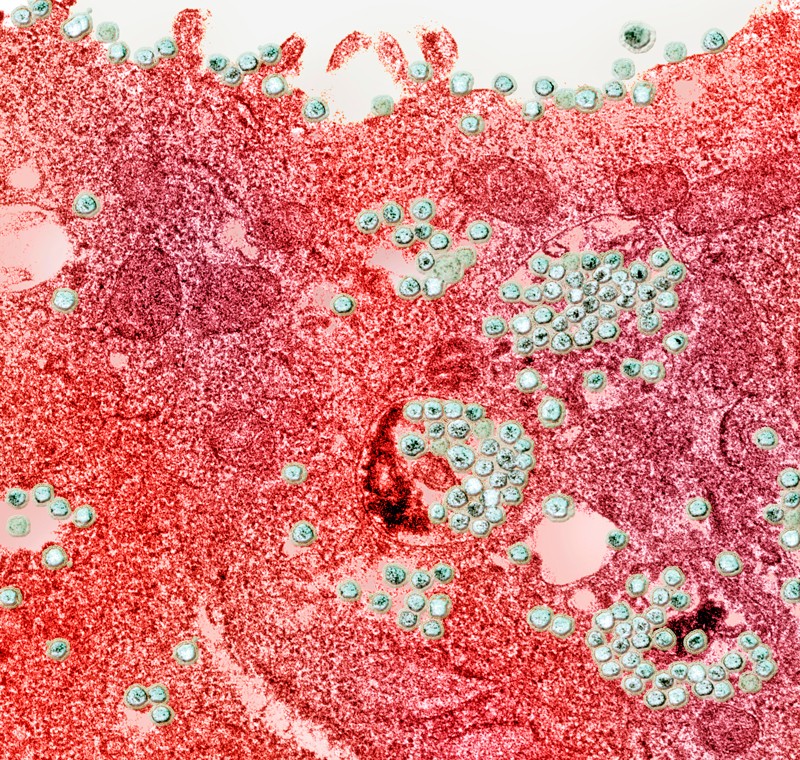

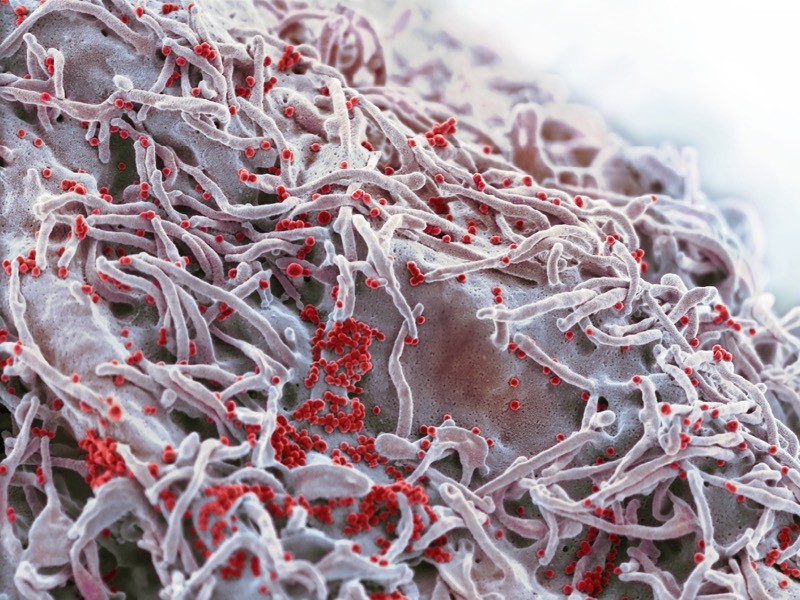

24 March — COVID-causing viruses are mixing in infected people’s cells

Different lineages of SARS-CoV-2 have been spotted mixing their genomes together through a process called recombination.

Recombination occurs when a cell is infected with multiple distinct viral lineages, and their genetic material gets mixed up as it’s copied. While analysing UK SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data, Ben Jackson at the University of Edinburgh and his colleagues detected several lineages that arose through recombination, which is common in coronaviruses.

All the lineages were products of recombination between the fast-spreading B.1.1.7 lineage, which contains 22 distinguishing mutations and started to become the dominant UK strain in late 2020, and other lineages circulating in the country. The team found evidence that four of the eight lineages identified had spread between individuals.

Six of the recombinant lineages contain the version of the spike gene — which encodes the protein that the virus uses to enter host cells — carried by the B.1.1.7 variant. This version of spike harbours mutations that might underlie the variant’s enhanced transmission. However, the researchers stress that there is no evidence that recombination has led to lineages that are altered in important ways, and the discovery of recombinant lineages does not have immediate implications for the course of the pandemic. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

19 March — Older people are at higher risk of getting COVID twice

An analysis of millions of coronavirus test results in Denmark suggests that natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 protects against reinfection in most people — but this protection is significantly weaker in those aged 65 years or older.

Steen Ethelberg and his colleagues at the Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen mined data from polymerase chain reaction tests, which are the gold-standard method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection, conducted in Denmark. The team focused on people who tested positive for the coronavirus during one or both of Denmark’s two surges of infection — from March to May and from September to December — in 2020.

The team found that, at about 6 months after initial infection, protection against repeat infection was approximately 80%, with no significant difference in reinfection rates between men and women. But this protection was reduced to 47% for those aged 65 years or older, emphasizing the need to prioritize vaccinations for this group.

17 March — Concerns emerge over a COVID vaccine’s prowess against a variant

A leading COVID-19 vaccine might offer only limited protection against a coronavirus variant first identified in South Africa.

A SARS-CoV-2 variant called B.1.351 (also known as 501Y.V2), which was first identified in South Africa in late 2020, has been linked to reduced efficacy for vaccines developed by Novavax and Johnson & Johnson. Now, in another unintentional test of the variant’s effects, Shabir Madhi at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and his colleagues conducted a South Africa-based trial of the vaccine developed by the University of Oxford, UK, and AstraZeneca. The trial involved around 2,000 people aged 18–64, who had tested negative for HIV and were randomly assigned to receive either the jab or a placebo.

The vaccine seemed to offer only 21.9% protection overall against the development of mild or moderate COVID-19, and just 10.4% against those cases caused by the B.1.351 variant. There were no cases of severe COVID-19 or hospitalization in either group, and the small size of the trial means the researchers can conclude only that the vaccine did not have an efficacy above 60% against B.1.351.

16 March — One mutation could explain a coronavirus variant’s rampage

A lone mutation might explain why a coronavirus variant that was identified in the United Kingdom has taken hold there and around the world.

In late 2020, researchers found a fast-spreading variant, called B.1.1.7, in southeast England. It now accounts for nearly all UK COVID-19 cases and a steadily rising proportion of those in Europe, North America and elsewhere. B.1.1.7 carries eight changes in the virus’s spike protein — which helps the virus to enter host cells — and it has not been clear which mutations might explain its rapid spread.

To better understand this, Pei-Yong Shi and Scott Weaver, at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, and their colleagues generated a bevy of SARS-CoV-2 strains, each with one of the individual spike mutations in B.1.1.7, as well as one carrying all eight. Strains with a mutation called N501Y replicated more quickly in the upper respiratory tracts of hamsters and in airway cells from humans, compared with the other strains, and they also spread more readily between animals.

Other mutations might contribute to the behaviour of B.1.1.7, the researchers say, but N501Y’s outsize effects on transmission make it one to watch for closely in other variants. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

12 March — A small piece of land yields bats with a trove of new coronaviruses

Bats in the province of Yunnan in southern China have yielded yet more coronaviruses closely related to the pandemic virus.

Weifeng Shi at the Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences in Taian, China, and his colleagues studied 302 samples of faeces and urine and 109 mouth swabs taken from 342 live bats between May 2019 and November 2020. The researchers trapped and released all the bats, which represented nearly two dozen species, in an area covering roughly 1,100 hectares — less than one-tenth the size of San Francisco, California.

From the samples, the team sequenced 24 coronavirus genomes, of which 4 were new viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2. One of the viruses isolated from a Rhinolophus pusillus bat shared 94.5% of its genome with the pandemic virus, making it the second-closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2. The closest known relative is a coronavirus called RATG13, which shares 96% of its genome with SARS-CoV-2 and was isolated from a Rhinolophus affinis bat in Yunnan in 2013.

The results suggest that viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 continue to circulate in bats and are highly prevalent in some regions, the researchers say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

11 March — Viral variant causes a more deadly form of COVID

People infected with the coronavirus variant called B.1.1.7 are at a higher risk of dying than are people infected with other circulating variants, regardless of their age, sex and pre-existing health problems.

Daniel Grint at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and his colleagues studied the health records of 184,786 people in England who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between 16 November 2020 and 11 January 2021. Of these individuals, 867 died by 5 February 2021.

The researchers found that for three people who died within a month of testing positive for a previously circulating viral variant, some five died after testing positive for B.1.1.7. The risk of death increases with age and the presence of pre-existing health problems, and men are at higher risk of dying than women.

First detected in the United Kingdom, B.1.1.7 is now the dominant variant there and is spreading widely across Europe. Without control measures and vaccines, the variant could cause a more deadly pandemic than previously circulating versions of the virus, the researchers say.

10 March — A worrisome coronavirus variant brings hope for better vaccines

People infected with a fast-spreading coronavirus variant mount an immune response that can fend off multiple SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Scientists first identified the SARS-CoV-2 variant called B.1.351 in South Africa in late 2020. They have since linked it to reinfections and found hints that several vaccines are less effective against it than against SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating earlier in the pandemic.

Penny Moore at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg, South Africa, and her colleagues assessed the antibody responses mounted by 89 people who were infected with B.1.351 and were admitted to hospital. The team found that these participants’ antibody levels were similar to those in people infected with earlier strains.

The team then pitted antibodies from people infected with B.1.351 against a form of HIV modified to use the coronavirus spike protein to infect cells. The antibodies were able to inactivate viruses incorporating the form of spike protein found in B.1.351, earlier strains, and an emerging variant identified in Brazil called P.1.

The results suggest that vaccines based on B.1.351’s genetic sequence might protect people from multiple strains of the coronavirus, the authors say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

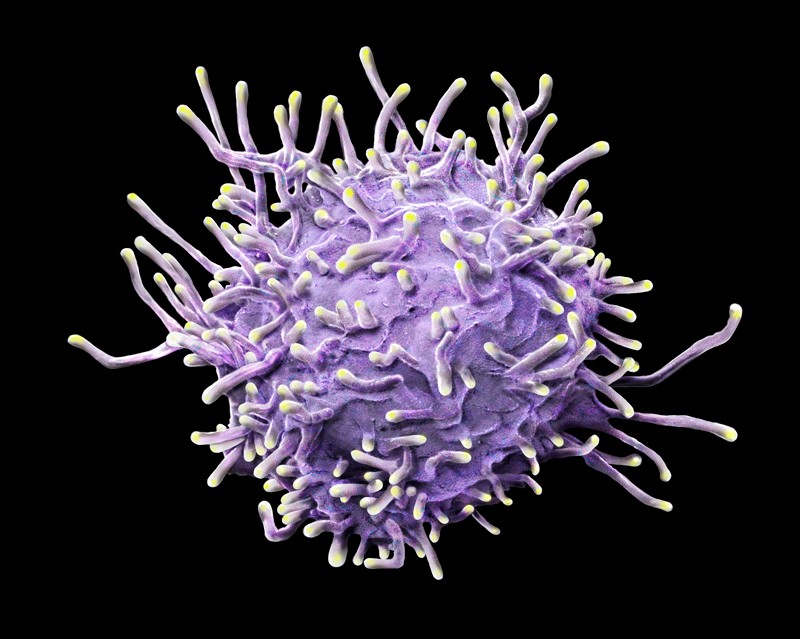

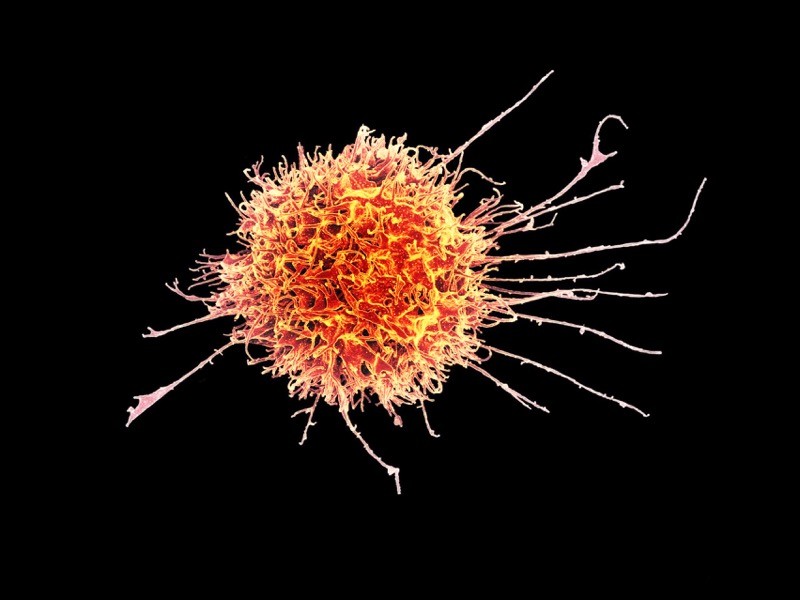

5 March — T cells might provide rescue from rampant coronavirus variants

Emerging coronavirus variants do not seem to elude important immune-system players called T cells, laboratory studies suggest.

Some recently discovered SARS-CoV-2 variants can partially evade antibodies generated in response to vaccination and previous infection,raising fears that vaccines will be less effective against the variants than against the original strain of the virus. Alessandro Sette and Alba Grifoni at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California and their colleagues looked at whether these variants’ mutations might also help them to evade T cells — a component of the immune system that is particularly important for reducing the severity of infectious diseases

The team collected T cells from volunteers who had either recovered from infection with the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain or had received an mRNA coronavirus vaccine. The researchers then tested the cells’ ability to recognize protein snippets from four emerging variants, including the B.1.351 variant first identified in South Africa.

Most of the volunteers’ T cells recognized all four variants, thanks to viral protein snippets that were unaffected by the variants’ mutations. The results suggest that T cells could target these variants.

4 March — A new viral variant hits a COVID-ravaged city

A coronavirus variant detected in the Brazilian city of Manaus might be driving reinfections and the city’s second wave of COVID-19.

During the first wave of the pandemic, Manaus experienced one of the world’s highest infection rates: an estimated two-thirds of residents were infected by October 2020, leading some researchers to predict that population-wide immunity might cause new infections to tail off. But in January 2021, researchers identified a novel coronavirus variant, called P.1, during a period of rising hospitalizations in the city and linked the variant to a few cases of reinfection.

To characterize the variant further, Nuno Faria, at Imperial College London, and his colleagues analysed viral genomes collected from 184 human samples in Manaus between November and December. The variant harbours 17 mutations that alter SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Among the alterations are changes in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that have been previously linked to increased transmission and immune evasion.

By modelling the spread of P.1 and its possible effects during Manaus’ second wave, the researchers estimated that the variant was 1.4–2.2 times more transmissible than other lineages and that it was able to evade some of the immunity conferred by previous infections. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

3 March — Kids in the classroom could mean COVID at home

Living with children who are attending school in person raises an adult’s risk of developing COVID-19 symptoms, but only if schools don’t implement appropriate control measures, according to a large online survey in the United States.

Justin Lessler at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues analysed responses to a Facebook survey completed in late 2020 and early 2021 by more than half a million people living with school-aged children; half of these respondents had children attending school in person, either full-time or part-time.

The researchers found that adults living with kids — especially high-school students — who went into school were more likely to report COVID-19 symptoms or test positive for SARS-CoV-2. But the researchers also found that schools could eliminate that risk entirely by implementing at least seven mitigation measures from a list that included requiring students and teachers to wear masks, preventing parents from entering schools and increasing the spacing between desks. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

2 March — Just one dose of vaccine protects against silent COVID infection

Asymptomatic coronavirus infections were four times less frequent in health-care workers who had received a single dose of a prominent COVID-19 vaccine than in their unvaccinated counterparts.

Michael Weekes at the University of Cambridge, UK, and his colleagues analysed the results of almost 8,900 SARS-CoV-2 tests taken by UK health-care workers without symptoms of COVID-19. Study participants who were tested at least 12 days after receiving one dose of the vaccine developed by Pfizer of New York City and BioNTech of Mainz, Germany, had an infection rate of only 0.2%. By contrast, unvaccinated participants had an infection rate of 0.8%.

The team also noted that participants who showed evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection well after vaccination tended to have lower levels of the coronavirus in their bodies than did those who were infected and unvaccinated, although the result did not reach statistical significance. If corroborated, this would suggest that the few vaccinated health-care workers who do have an asymptomatic infection are less likely to infect other people than are unvaccinated workers who become infected.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

26 February — A COVID vaccine passes a real-world test with flying colours

The two-shot Pfizer vaccine is highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19, according to an analysis of more than one million people in Israel.

Ran Balicer at Clalit Health Services in Tel Aviv, Israel, and his colleagues matched 596,618 people vaccinated as part of a nationwide campaign with an unvaccinated ‘twin’ of the same age, sex, ethnicity and neighbourhood of residence. The pairs also had a matching number of medical conditions and shared other characteristics (N. Dagan et al. N. Engl. J. Med.

The researchers found that, at 7 days or more after the second shot, Pfizer’s vaccine was 94% effective at preventing COVID-19 and 92% effective against severe disease. The results were consistent across all age groups, including in people aged 70 and older. The results were strikingly close to efficacy estimates from clinical trials, despite being based on jabs administered in less stringently controlled settings and more diverse populations, including people with multiple health problems.

The study also covered a period when the emerging variant called B.1.1.7 was circulating widely in Israel, which suggests that the vaccine is effective at preventing COVID-19 caused by that variant.

25 February — Trial hints that Pfizer vaccine could curb COVID transmission

A leading COVID-19 vaccine is highly effective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections, whether they cause symptoms or not — the strongest evidence yet that vaccines could control viral spread.

Large-scale trials of COVID-19 vaccines have focused on assessing their ability to prevent disease, but researchers also want to know whether the vaccines can prevent people from getting infected, even if they show no symptoms. Susan Hopkins at Public Health England in London and her colleagues tracked the effectiveness of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech in 23,000 UK health-care workers who were already part of a long-term study of SARS-CoV-2 immunity Participants were tested regularly for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of their symptoms.

The vaccine was 70% effective at preventing both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in the period beginning 3 weeks after the first dose; this grew to 85% shortly after a second dose of the RNA vaccine. This finding is the first evidence that Pfizer’s vaccine might block transmission, the researchers say. The study has not yet been peer reviewed.

23 February — Viral variant is less susceptible to a COVID vaccine’s effects

Coronaviruses engineered to contain mutations from a worrisome variant partially blunt the immune protection offered by a prominent vaccine.

In recent months, studies have raised the possibility that the potent antibodies summoned by vaccines could be less effective against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants than against older versions of the virus. Most of this work stems from experiments not on SARS-CoV-2, but on viruses such as HIV that have been modified to contain SARS-CoV-2’s signature spike protein.

Pei-Yong Shi at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston and his colleagues engineered several variants of SARS-CoV-2, including one containing the same spike-protein mutations as a troubling variant called B.1.351 (also known as 501Y.V2) that was first identified in South Africa (Y. Liu et al. N. Engl. J. Med.

The team pitted the B.1.351-like virus against blood serum from people who had received two doses of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech in Mainz, Germany. Antibodies elicited by the vaccine neutralized the virus only one-third as effectively as they did a strain lacking those mutations.

The researchers traced most of the virus’s evasive ability to a trio of mutations in the portion of the spike protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to adhere to host cells. However, it is not clear whether these changes make the vaccine less effective at preventing COVID-19.

22 February — A delayed second jab means better protection against COVID

A widely used COVID-19 vaccine is more effective if the second of its two doses is given after a long wait rather than a short one — a finding that supports a decision by UK public-health officials to space out the doses.

The two-dose vaccine developed by the University of Oxford, UK, and pharmaceutical firm AstraZeneca in Cambridge, UK, could be given to more people by lengthening the interval between jabs. To test the efficacy of this strategy, Andrew Pollard at the University of Oxford and his colleagues examined clinical-trial data from more than 17,000 people, half of whom received the vaccine and the other half a placebo (M. Voysey et al. Lancet

The team found that, for intervals greater than six weeks, the longer the gap between jabs, the better the vaccine protected against COVID-19. It was 55% effective in those who received their second dose less than 6 weeks after their first, and 81% effective in those whose second dose was more than 12 weeks after their first. The team also found that a single dose of the vaccine had an efficacy of 76% for the first 90 days after vaccination.

19 February — Longer infections could fuel a variant’s quick spread

Preliminary findings suggest that B.1.1.7, a SARS-CoV-2 variant first identified in the United Kingdom, might be more transmissible because it spends more time inside its host than earlier variants do.

Previous studies have estimated that B.1.1.7, which is now spreading rapidly in a number of countries, is roughly 50% more contagious than earlier coronavirus variants are. Yonatan Grad at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues examined the results of daily SARS-CoV-2 tests on 65 people infected with SARS-CoV-2, including 7 infected with B.1.1.7 (S. M. Kissler et al. Preprint at https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37366884; 2021). The team looked at how long the virus persisted, and the amount of virus present at each time point.

In people infected with B.1.1.7, infections lasted an average of 13.3 days, compared with 8.2 days in people with other variants. There was little difference in the peak concentrations of the virus between the two groups.

These findings hint that B.1.1.7 is more easily transmitted than other variants are because people who catch it are infected for a relatively long time, and can therefore infect a larger number of contacts. This suggests that longer quarantine periods might be warranted for individuals infected with this variant. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

16 February — ‘Robin’ leads a flock of new US COVID variants

Seven newly identified coronavirus variants in the United States share a similar mutation, but the significance of this change is not yet clear.

Coronavirus variants emerging in a range of geographical locations seem to share certain mutations — possible evidence that the changes aid transmission. Jeremy Kamil at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport and his colleagues identified a new variant that they named Robin. It carries a change called Q677P in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which the virus uses to bind to cells.

The lineage was first spotted in October and its prevalence has risen in some parts of the United States. It accounted for 27.8% of sequenced viruses in Louisiana and 11.3% in New Mexico between the start of December 2020 and mid-January 2021. The researchers identified six other variants — also named after birds, including Pelican and Bluebird — in the United States with a mutation at the same spot in the spike protein.

The mutation is located near a portion of the spike protein that must be cut to allow a viral particle to infect a cell, but the researchers say that laboratory studies might be needed to determine what the mutation does. The finding has not yet been peer reviewed.

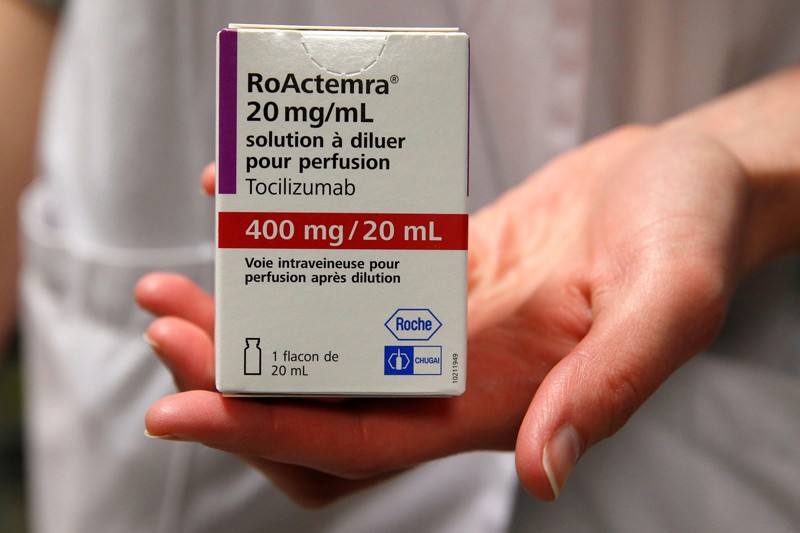

15 February — Drug can be a lifeline for people hospitalized for COVID

An anti-inflammatory drug can save the lives of people hospitalized for COVID-19 whose immune systems have gone into overdrive against the coronavirus. The drug also cuts the need for invasive ventilation, according to a large study.

Many people with severe COVID-19 symptoms show evidence of widespread inflammation. The drug tocilizumab is designed to dampen such an immune response, but previous clinical trials of its benefits in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 have been equivocal.

Peter Horby and Martin Landray at the University of Oxford, UK, and their colleagues compared more than 2,000 people treated with tocilizumab with a similar number who did not receive the drug. Study participants were in hospital and receiving oxygen and had evidence of system-wide inflammation, and nearly all were also taking the steroid dexamethasone.

The authors report that 54% of people who received tocilizumab left hospital within 28 days, compared with 47% of those not taking the drug. An analysis showed that tocilizumab provided benefits on top of those from dexamethasone. The team estimates that roughly half of all people hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United Kingdom would benefit from the drug.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

12 February — Vaccines spur antibody surge against a COVID variant

One shot of either the Moderna or the Pfizer vaccine provokes a strong immune response against an emerging variant of SARS-CoV-2, according to tests in people who have recovered from COVID-19.

The mRNA vaccines made by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Pfizer in New York City are highly effective at preventing COVID-19 caused by the original form of SARS-CoV-2. Andrew McGuire at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues collected blood from ten people who had recovered from COVID-19; they collected additional samples after the study participants had received a single dose of one of the two vaccines (L. Stamatatos et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ft9j; 2021). The researchers then examined the participants’ levels of neutralizing antibodies — which defend cells from infection — against the original version of SAR-CoV-2, which was first detected in Wuhan, China, and against B.1.351, the concerning new variant that was first identified in South Africa.

Before inoculation, nine of the ten individuals had neutralizing antibodies against the original virus, although the levels generated were highly variable. Antibodies from only five people could neutralize B.1.351. Following a single shot of the vaccine, however, participants’ levels of neutralizing antibodies against both forms of the virus increased by approximately 1,000-fold.

9 February — Nimble coronaviruses could leap straight from bats to humans

Some coronaviruses found in bats could jump directly to people without the need for further evolution in an intermediate animal host.

Victor Garcia at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his colleagues implanted mice with human lung tissue and infected the tissue with various coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and two closely related coronaviruses isolated from bats. All of the viruses could efficiently multiply in the lung tissue.The findings suggest that coronaviruses circulating in bats could directly infect people, and have the potential to cause the next pandemic.

The researchers also used the animal model to show that an oral antiviral drug known as EIDD-2801 could significantly reduce infectious particles of SARS-CoV-2 in the lung tissue. They say that the drug, currently in late-stage clinical trials, could be used to prevent disease as well as to treat people within a day or two of exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

8 February — Why it matters that COVID viruses are losing parts of their genome

Again and again, the new coronavirus has sloughed off small chunks of its genome, leading to changes in a viral protein that is frequently targeted by antibodies.

When evolution snips out a stretch of an organism’s genome, the change is called a deletion. Kevin McCarthy and Paul Duprex at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pennsylvania and their colleagues searched a database of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences and identified more than 1,000 viruses with deletions in the genomic region that encodes a protein called spike. The virus uses the spike protein to invade cells.

Further analysis showed that the deletions tended to crop up at a few distinct sites in the genomic region coding for spike. Some of the deletions have arisen independently multiple times, and some show evidence of spread from one person to another.

A powerful antibody against SARS-CoV-2 could not latch onto spike proteins harbouring some of the deletions that the team identified. But antibody mixtures collected from people who had recovered from COVID-19 could disable viral variants that had deletions.

5 February — One man’s COVID therapy drives worrisome viral mutations

Antibody treatment for COVID-19 seems to have spurred mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 that infected a man with a compromised immune system.

In mid-2020, a man was admitted to hospital with COVID-19. He had been diagnosed with cancer in 2012; the illness and his treatment had probably weakened his immune system. The man’s COVID-19 was treated with two courses of the antiviral drug remdesivir and, later, two courses of convalescent plasma — antibody-laden blood from people who had recovered from COVID-19. He died 102 days after admission.

Ravindra Gupta at the University of Cambridge, UK, and his colleagues analysed viral genomes obtained from the man during his illness. The viral populations in his blood changed little after remdesivir treatment. But after each course of convalescent plasma, the samples were dominated by viruses with a particular pair of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, the main target of the immune system.

Experiments showed that one of the mutations weakened the potency of the antibodies in the convalescent plasma, yet also reduced the virus’s infectivity. The second mutation restored infectivity. The potential for viral evolution means that convalescent plasma should be used cautiously when treating people with compromised immunity, the authors say.

4 February — What makes a person with COVID more contagious? Hint: not a cough

The amount of SARS-CoV-2 in a person’s body is a major factor in determining whether they are likely to transmit the virus to others, according to a study of nearly 300 infected people and their close contacts.

Most people with COVID-19 do not give it to anyone else, but some become ‘superspreaders’. To understand why, Michael Marks at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and his colleagues monitored 282 people, deemed ‘index cases’, who had recently developed mild symptoms of COVID-19. The team also monitored 753 people who lived with, cared for or otherwise had close contact with the index cases (M. Marks et al. Lancet Infect.

Only one-third of the index cases transmitted the virus to a close contact. Those with a relatively high ‘viral load’, a measure of the amount of virus in the body, were much more likely to pass on the virus than were those with a low viral load. Index cases were no more likely to transmit the virus if they had a cough than if they didn’t.

The findings suggest that tracing the contacts of people with high viral loads is especially important, the authors say.

2 February — Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine shows high effectiveness

A vaccine that relies on modified cold viruses is more than 91% effective against symptomatic COVID-19, according to interim results of a clinical trial involving nearly 22,000 people.

Pathogens in the adenovirus group typically cause mild illnesses, such as the common cold. The Sputnik V vaccine developed at the Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology in Moscow consists of two types of adenovirus, each carrying genetic instructions for the spike protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to latch onto host cells. Use of two viruses could help to increase the immune response to the vaccination.

Denis Logunov at the Gamaleya centre and his colleagues analysed data from roughly 15,000 clinical-trial participants who had received an initial jab containing one type of adenovirus and, 21 days later, a booster jab of the second type of virus. The team also studied 4,900 participants who received two doses of a placebo.

Starting from 21 days after the first jab, 16 symptomatic cases of COVID-19 — all mild — were recorded in the vaccine group. The placebo group incurred 62 cases, 20 of which were moderate or severe.

Preliminary evidence suggests that the vaccine starts to offer protection 16–18 days after the first dose, but the authors say more research is needed to confirm this early finding.

29 January — An antibody that clamps onto the COVID virus’s ‘Achilles heel’

Scientists have engineered an antibody that effectively disables SARS-CoV-2 and closely related coronaviruses.

Laura Walker at the biopharmaceutical company Adimab in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and her colleagues isolated antibodies from the immune cells of a person who had recovered from a 2003 infection with the virus SARS-CoV, which is related to SARS-CoV-2. By tinkering with the structure of the antibodies, the researchers created one, called ADG-2, that was particularly effective at disabling SARS-CoV-2 in a lab dish.

The engineered antibody also disabled a variety of related coronaviruses. When given to mice, it stopped SARS-CoV-2 from reproducing in the rodents’ lungs and protected the animals from respiratory disease.

Experiments showed that ADG-2 targets receptors found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 and a range of similar coronaviruses. The authors dub this receptor the Achilles heel of coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, and suggest that this vulnerability could be exploited to make vaccines against emerging coronaviruses.

28 January — The workers who keep us fed face some of the highest COVID risk

The death risk for essential workers in some sectors was 20–40% higher than expected during the first 8 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an analysis of death records in California.

Yea-Hung Chen and his colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, analysed state data for people aged 18–65 to estimate how many more deaths occurred among working-age adults during the pandemic than would have been expected without the onslaught of SARS-CoV-2. The team found that compared with a no-pandemic scenario, deaths were 39% higher for food and agriculture workers, 28% higher for transportation and logistics workers and only 11% higher for non-essential workers.

The workers with the highest COVID-related risk included cooks, bakers, agricultural labourers and people who pack and prepare goods for shipment. Risk also varied by race and ethnicity: compared with the no-pandemic scenario, mortality during the pandemic was 36% higher for people aged 18–65 of Latin American descent overall and 59% higher for food and farm workers in this group.

The authors say essential workers should receive free personal protective equipment and easy access to testing. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

26 January — Moderna vaccine vanquishes viral variants

A leading COVID-19 vaccine seems to work against new, rapidly spreading variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Darin Edwards at biotechnology company Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues collected blood samples from 8 people and 24 macaques that had received 2 doses of the company’s vaccine. The vaccine instructs the body to make the coronavirus’s spike protein, priming the immune system to produce ‘neutralizing’ antibodies that can prevent cells from being infected. All of the blood samples from vaccinated people and monkeys contained neutralizing antibodies against the virus.

The researchers exposed the blood to viral particles that mimic a range of coronavirus variants, including an emerging form first found in the United Kingdom and another, 501Y.V2, first detected in South Africa. The samples’ neutralizing antibodies were as effective against the variant first found in the United Kingdom as against an older form of the virus, but only about one-fifth to one-tenth as effective at neutralizing 501YV.2. Even so, the antibodies were effective enough to provide protection against both variants, the authors say.

Moderna says it plans to test a booster to enhance immunity to emerging coronavirus variants. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

21 January — COVID vaccines might lose potency against new viral variants

Newly emerging, fast-spreading variants of the coronavirus might reduce the protective effects of two leading vaccines.

Michel Nussenzweig at the Rockefeller University in New York City and his colleagues analysed blood from 20 volunteers who received two doses of either the vaccine developed by Moderna or that developed by Pfizer–BioNTech. Both vaccines carry RNA instructions that prompt human cells to make the spike protein that the virus uses to infect cells. This causes the body to generate immune molecules called antibodies that recognize the spike protein.

Within 3–14 weeks after the second jab, the study participants developed several types of antibody, including some that can block SARS-CoV-2 from infecting cells. Some of these neutralizing antibodies were as effective against viruses carrying certain mutations in the spike protein as they were against widespread forms of the virus. But some were only one-third as effective at blocking the mutated variants.

Some of the mutations that the team tested have been seen in coronavirus variants that were first identified in the United Kingdom, Brazil and South Africa; at least one of these variants is more easily transmitted than other forms of the virus now in wide circulation.

The findings suggest that vaccine-resistant variants might emerge, meaning that COVID-19 vaccines could need an update. They have not yet been peer reviewed.

20 January — The unsung viral feature that could lead to more COVID treatments

A usually overlooked region of a key SARS-CoV-2 protein is an important chink in the virus’s armour.

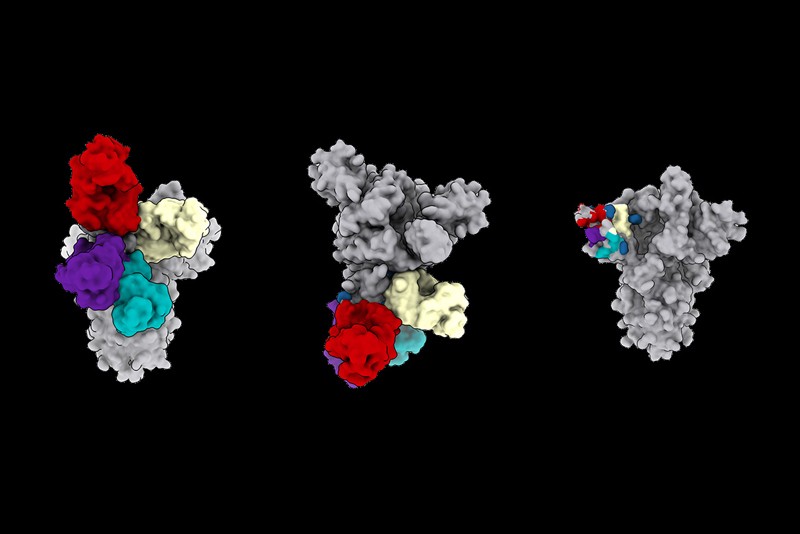

Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 block particles of the virus, which makes them some of the body’s most potent weapons against the new pathogen. Most of the neutralizing antibodies that researchers have studied target a region of the virus’s spike protein called the receptor-binding domain (RBD). But previous studies have also identified neutralizing antibodies that act against other portions of spike — particularly a region called the N-terminal domain (NTD).

David Veesler at the University of Washington in Seattle and his colleagues analysed the blood of people who had recovered from COVID-19, and identified 41 antibodies that recognize the NTD. Some proved to be as potent at blocking infection as were antibodies that recognize the RBD. Hamsters treated with one of the strongest NTD-targeting antibodies were protected from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Worryingly, the authors found that variants of the coronavirus first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa carry mutations that might weaken the effects of some NTD antibodies. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

19 January — Immune cells ‘remember’ COVID for at least half a year

The immune system remembers how to make antibodies that can fend off the new coronavirus for at least six months after the initial infection.

Levels of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 often wane in the months following infection, which has raised concerns that immunity to the virus declines rapidly. Michel Nussenzweig at the Rockefeller University in New York City and his colleagues collected blood samples from 87 people about 1 month and 6 months after they were infected with the virus. The team monitored participants’ levels of antibodies and memory B cells, immune cells that would stimulate the production of antibodies against the virus if the study participants were reinfected.

The team found that levels of antibodies against the coronavirus’s spike protein declined over six months. But participants’ levels of memory B cells specific for making antibodies against the spike protein remained constant. The researchers sampled the intestines of 14 participants 4 months after infection and found that half had persistent SARS-CoV-2 protein or RNA, potentially providing a continued source of stimulation to the immune system.

15 January — Two anti-inflammatory drugs prevent COVID deaths

Two drugs that dampen the body’s immune response can save the lives of people with severe COVID-19.

Some people gravely ill with COVID-19 have tissue damage inflicted by their own immune response, and also show increased activity of immune-system molecules and cells regulated by a protein called IL-6. To study the effect of quashing IL-6 activity, Anthony Gordon of Imperial College London and his colleagues tested the drugs tocilizumab and sarilumab, which block the protein that immune cells use to detect IL-6.

The team gave the drugs to 803 adults with COVID-19 who were in intensive care and receiving organ support, such as ventilation or high-flow oxygen. Of these participants, 353 received tocilizumab, 48 received sarilumab and 402 received neither. The drug treatment reduced the death rate — from nearly 36% in the control group to 28% among those who received tocilizumab and 22% for sarilumab.

The results have not yet been peer reviewed.

14 January — A potential COVID vaccine causes a durable immune response

A candidate vaccine spurs both younger and older people to make antibodies against the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, according to early trial results.

The vaccine, which is under development by Johnson & Johnson, headquartered in New Brunswick, New Jersey, uses a harmless virus to inject cells with the instructions for making the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Hanneke Schuitemaker at Janssen Vaccines and Prevention in Leiden, the Netherlands, and her colleagues tested the vaccine’s safety and immune-stimulating properties in more than 800 people aged 18 years and up.

Almost 100% of study participants aged 18–55 years had developed potent antibodies against the virus 57 days after receiving a single low dose of the jab. In a separate arm of the trial, the same regimen triggered the development of antibodies in 96% of participants aged 65 years and older 29 days after vaccination. Side effects were largely mild or moderate, and antibodies persisted until at least 71 days after inoculation.

The results of larger efficacy trials of the vaccine are pending.

13 January — A mutation undercuts the immune response to the COVID virus

A handful of mutations to SARS-CoV-2 can help it to escape the immune response mounted by a subset of infected people.

Researchers have identified thousands of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 samples, but the vast majority are unlikely to have much effect on the virus’s biology. To identify potentially important mutations, Jesse Bloom at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues studied antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 isolated from the blood serum of people who had recovered from COVID-19.

The team tested the antibodies’ response to samples of the virus’s spike protein. Each sample protein carried different versions of a region called the receptor binding domain (RBD), which recognizes host cells and is a major target for antibodies.

Of thousands of RBD mutations tested, only a few reduced the antibodies’ ability to bind tightly to the spike protein — a change that might also indicate a reduction in the antibodies’ ability to disable the virus.

But the effects varied substantially between people. The most consequential mutations, at a location called E484, caused a steep drop in the potency of some individuals’ antibodies. Coronavirus variants identified in South Africa and Brazil carry a mutation at the same spot.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

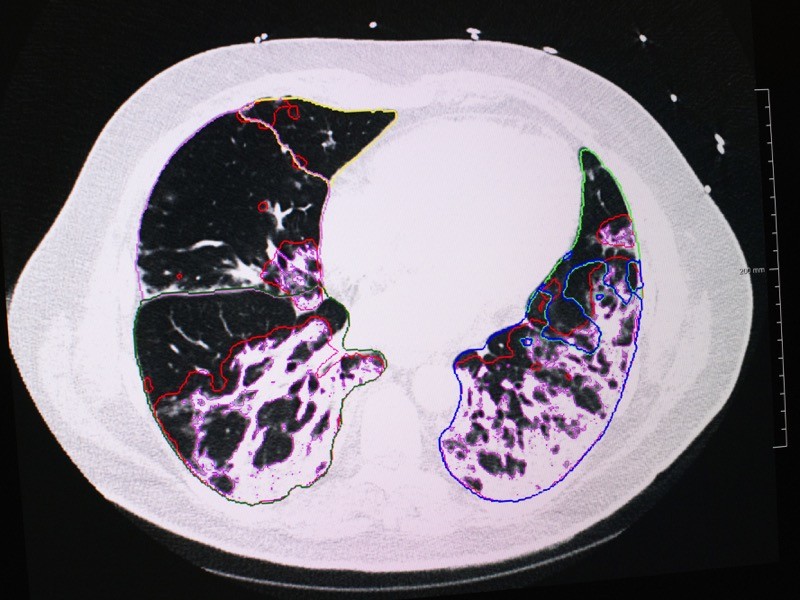

12 January — Immune cells gone wild are tied to COVID lung damage

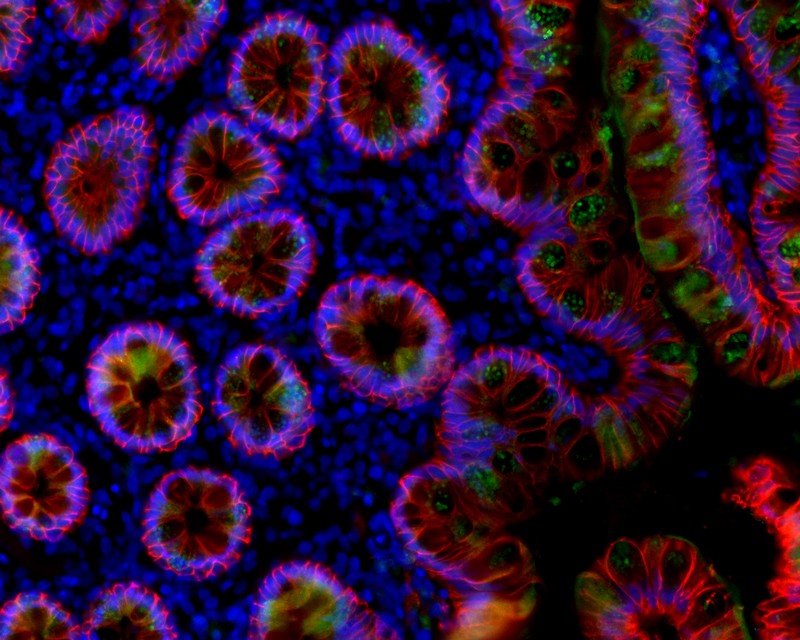

Some of the severe respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 seem to result from the activity of specific immune cells, which can cause long-term inflammation of the lungs.

Alexander Misharin at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues examined fluid from the lungs of 88 people with severe pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Most of these individuals had high numbers of a certain type of T cell, a class of immune cells, in their lungs. The researchers also found that nearly 70% of alveolar macrophages, a type of immune cell that is located in the tiny air sacs of the lungs, contained SARS-CoV-2. The cells harbouring the virus showed relatively high expression of genes involved in inflammation.

The findings suggest that, once the virus reaches the lungs, it can infect macrophages, which respond by producing inflammatory molecules that attract T cells. T cells, in turn, produce a protein that stimulates macrophages to make more inflammatory molecules. This persistent lung inflammation could lead to some of the life-threatening consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

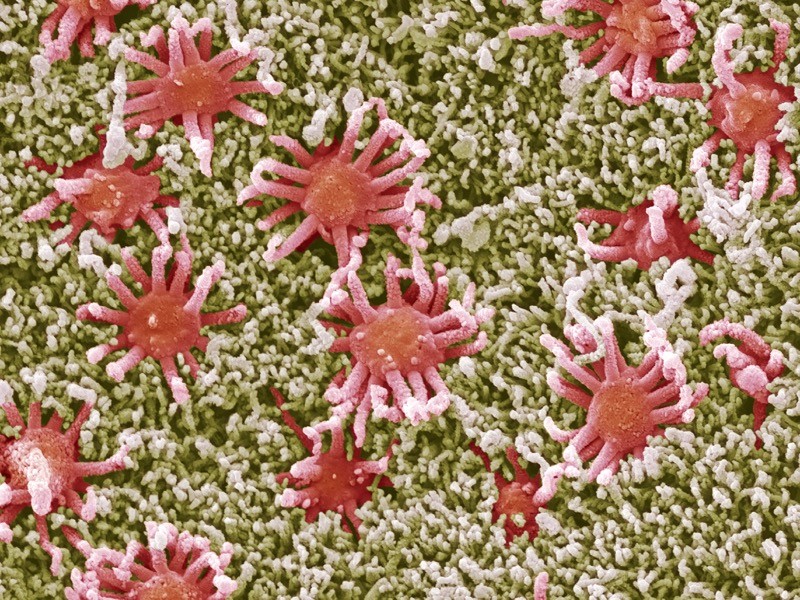

11 January — Traitorous antibodies are linked to COVID death

Antibodies normally attack pathogens, but, sometimes, rogue antibodies instead besiege bodily components such as immune cells. Now, a new study adds to the growing body of research tying these ‘autoantibodies’ to poor outcomes in people with COVID-19.

Ana Rodriguez and David Lee at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City and their colleagues studied autoantibody levels in blood serum collected from 86 people who required hospitalization for COVID-19. The researchers were particularly interested in autoantibodies against the protein annexin A2, which helps to stabilize cell-membrane structure. It also plays a part in ensuring the integrity of tiny blood vessels in the lungs. Blocking annexin A2 leads to lung injury, a hallmark of COVID-19.

The scientists found that the level of anti-annexin A2 antibodies was, on average, higher in the individuals who eventually died of COVID-19 than in those who survived — a difference that was statistically significant.

More research is necessary to establish a clear causal link between the virus SARS-CoV-2 and autoantibodies against annexin A2, which are relatively rare. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

8 January — Quick treatment with antibody-laden blood cuts risk of severe COVID

A clinical trial in older adults with COVID-19 shows that an early dose of blood plasma from recovered people helps to prevent the progression to severe disease.

The plasma of people who have recovered from COVID-19 contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. But treatment with such plasma has had mixed results, and some scientists have suggested that plasma needs to be given early in the disease course to be effective. Fernando Polack at Fundación INFANT in Buenos Aires and his colleagues conducted a rigorous clinical trial to assess the effect of treatment with plasma within 72 hours of symptom onset. Participants included people over the age of 75 and those between 65 and 74 with at least one pre-existing condition such as diabetes.

Severe COVID-19 developed in 16% of the 80 study participants who received plasma and 31% of the 80 participants in the placebo group. The team found that donor plasma containing higher concentrations of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 was associated with a greater reduction in the risk of developing severe disease — providing evidence that the antibodies themselves are responsible for the therapeutic effect.

7 January — Evidence grows of a new coronavirus variant’s swift spread

Two independent analyses have found that a new SARS-CoV-2 variant overtaking the United Kingdom is indeed more transmissible than other forms of the virus.

Eric Volz and Neil Ferguson at Imperial College London and their colleagues examined nearly 2,000 genomes of the variant, which has been labelled variant of concern 202012/01. The genomes were collected in the United Kingdom between October and early December 2020. The team also analysed the results of roughly 275,000 UK COVID-19 tests administered in late 2020.

Estimating the variant’s frequency over time, the authors concluded that it is roughly 50% more transmissible than other variants. The authors also found that a UK lockdown in November curbed COVID-19 cases caused by most viral variants — but cases linked to the new variant rose. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

A separate team also used genomic and other data to analyse the variant’s spread in the last few months of 2020. Nicholas Davies and his colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimated that the new variant is 56% more transmissible than other variants. The authors found no evidence that the variant of concern causes more severe COVID-19 than other variants. The findings are now under peer review.

6 January — A less-sensitive COVID test could help to curb outbreaks

Rapid COVID-19 tests that trade away a degree of reliability for speed could prove a valuable public-health tool in communities that are hit hard by the disease.

Fast coronavirus tests: what they can and can’t do

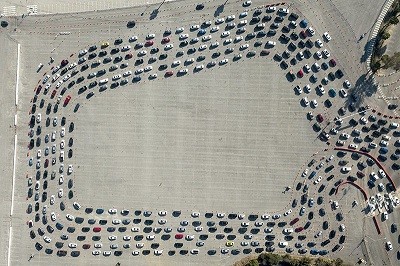

In one week, Diane Havlir at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues tested about 3,300 people in the city for SARS-CoV-2. All the study volunteers had two tests: the gold-standard PCR test, which typically returns results in two to four days in the United States; and a rapid test that detects viral proteins called antigens and returned results in roughly one hour. The rapid test, BinaxNOW, is made by Abbott Laboratories in Abbott Park, Illinois.

The rapid test detected 89% of the 237 people who tested positive with PCR — and it detected all of those who had high levels of the virus. Within two hours of a positive rapid-test result, participants received a phone call advising them to isolate themselves. This swift response meant people were less likely to spread the infection than they might have been had they waited for a PCR result. Approximately 1% of the positive rapid antigen tests were not confirmed by PCR — meaning they were wrong.

Study author Havlir disclosed that she receives non-financial support from Abbott that is not related to the paper.

4 January ― A vaccine works quickly to ward off COVID-19

An RNA-based vaccine recently approved by US regulators can provide protection against COVID-19 within two weeks of the first dose, according to the results of a large clinical trial.

On 18 December, the US Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency-use authorization to a vaccine made by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter, Lindsey Baden at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Hana El Sahly at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and their colleagues published the results of a vaccine trial that enrolled more than 30,000 volunteers. Half received two doses of a placebo and half received two doses of the vaccine, 28 days apart.

The vaccine was 94% effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19, and preliminary analysis hints that just one dose of the vaccine might also provide some defence against asymptomatic disease, the authors write. All 30 trial participants who developed severe COVID-19 were in the placebo arm.

About half of volunteers who received the vaccine experienced side effects such as headaches after their second dose. But serious side effects were rare and occurred as frequently in the placebo group as in the vaccinated group.

21 December — How 90% of French COVID cases evaded detection

In the weeks after France ended its first lockdown, nine residents with COVID-19 symptoms went undetected for every person confirmed to have the disease — despite a nationwide surveillance programme.

France reopened in May but adopted a strategy of testing, contact tracing and case isolation to keep the coronavirus in check. To assess the results, Vittoria Colizza at the Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health in Paris and her colleagues modelled COVID-19 transmission in France between mid-May and late June. They found that the national testing campaign missed some 90,000 people with COVID-19 who showed symptoms at a time when infections in the country were declining.

The findings show that a low rate of positive test results does not always equate to a high rate of detected cases. The results also suggest that many people with symptoms of COVID-19 did not seek medical advice or testing.

Countries need to implement more aggressive and efficient testing of people with suspected infections if surveillance is to be a useful tool for fighting the pandemic, the researchers say.

18 December — Stay-at-home orders have limited value for curbing COVID

An analysis of COVID-19 data from 41 countries has identified 3 measures that each substantially cut viral transmission: school and university closures, restricting gatherings to no more than 10 people and shutting businesses. But adding stay-at-home orders to those actions brought only marginal benefit.

Questions linger about the relative effectiveness of specific measures to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. To pinpoint the most useful, Jan Brauner at the University of Oxford, UK, and his colleagues modelled the number of new SARS-CoV-2 infections in 41 countries between 22 January and either 30 May or the first easing of restrictions. The team also examined when each country implemented seven common anti-transmission measures.

By combining the two data sets, the researchers found that closing schools and universities had a “large effect” in dampening viral spread. Most countries closed schools and universities in quick succession, making it impossible for the team to disentangle the effects of each type of closure.

In countries that closed schools and businesses and restricted gatherings, a stay-at-home order did little more to reduce transmission, the authors found.

16 December — Self-sabotaging antibodies are linked to severe COVID

Antibodies usually fight off infection, but occasionally the immune system makes some that erroneously attack the body’s own organs and even the immune system itself. New results show that these ‘autoantibodies’ might explain why some people have a severe reaction to infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Akiko Iwasaki and Aaron Ring at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and their colleagues studied 194 people with COVID-19 and found that the most seriously ill had high levels of autoantibody activity. Some of the autoantibodies attacked the body’s immune cells, hampering the ability to fight off infection. Others attacked the central nervous system, the heart, the liver or connective tissue.

No single autoantibody was common enough to be used to distinguish people with COVID-19 from uninfected people. The authors say the diversity of autoantibodies could explain the various disease states that follow COVID-19.

14 December — A drug duo that helps people with severe COVID

A combination of the drugs baricitinib and remdesivir shaved one day off the recovery of people hospitalized with COVID-19.

The US National Institutes of Health recommends remdesivir as a treatment for some people with COVID-19. But questions linger about remdesivir’s effectiveness, and the World Health Organization cautions against its use.

To test it as part of a combination therapy, Andre Kalil at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha and his colleagues gave remdesivir and the anti-inflammatory drug baricitinib to roughly 500 people hospitalized with moderate or severe COVID-19. Some 500 people in a control group received remdesivir and a placebo. The team monitored how long it took participants to recover enough to go without sustained medical care.

Those who took both drugs had a median time to recovery of seven days, compared with eight days for those who took only remdesivir. But for people who were on the edge of requiring invasive ventilation, median recovery time fell from 18 days on remdesivir alone to 10 days on both drugs.

11 December — How to save the most lives when a COVID vaccine is scarce

Front-line health-care workers will probably be the first to get COVID-19 vaccines, but who should be next in the queue when supplies are limited? Models suggest that it should be elderly people.

Kate Bubar and Daniel Larremore at the University of Colorado Boulder and their colleagues modelled the effects of rolling out a vaccine if various age groups are given priority. The researchers also examined the influence of the rate of viral spread in the population, the speed of vaccine delivery and the effectiveness of the protection offered by the vaccine.

The team found that in most scenarios, giving the jabs to people older than 60 before those in other age groups saved the greatest number of lives. But to prevent as many people as possible from getting infected, countries should prioritize younger age groups, according to the analysis.